“I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.” (Exodus 20:2, ESV)

In my last post (Part 1), we considered the archaeological evidence for Hebrew slaves in Egypt before the time of the Exodus. That is significant, but what kind of evidence supports the Exodus event itself?

According to the biblical book of Exodus, when God commissioned Moses for the task of delivering His people out of bondage, Moses was told that Pharaoh would refuse to let the people go, but that there was a purpose to this.

The Lord instructed Moses, “When you go back to Egypt, make sure you do all the wonders before Pharaoh that I have put within your power. But I will harden his heart so that he won’t let the people go.” (Exodus 4:21, HCSB)

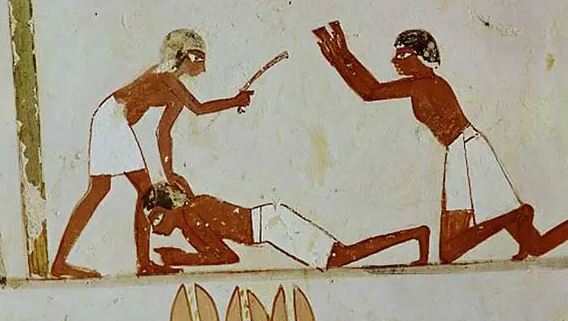

Sin always grieves God, and a hard heart stands in opposition to His holy ways. However, the God who works all things together for good (Romans 8:28) wisely used Pharaoh’s stubborn hardheartedness as an occasion to show His glory over the false gods of Egypt. And so God sent ten mighty plagues on the land of Egypt, beginning with Yahweh turning the Nile River into blood. From then on, each plague (frogs, gnats, hail wiping out grain, skin disease, etc.) escalates in magnitude of national devastation. And each time God spares His chosen people from these disasters.

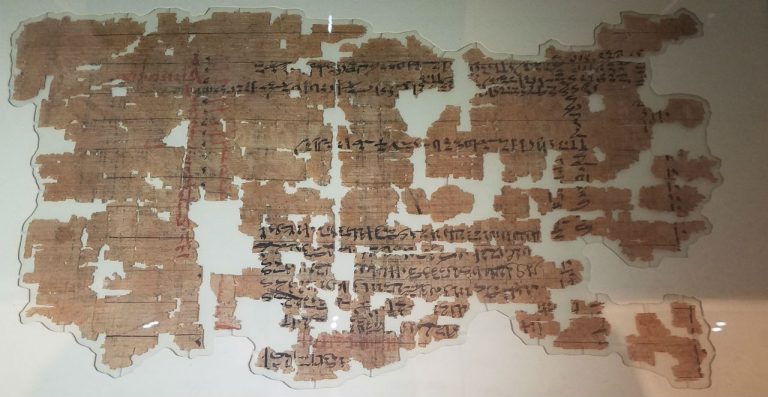

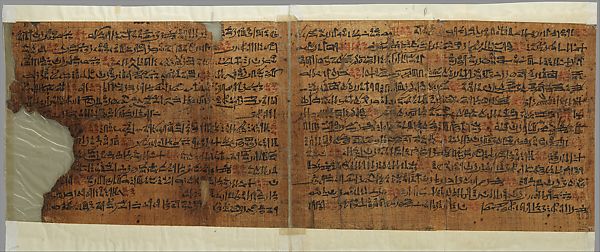

The Ipuwer Papyrus

While many scholars have tried to come up with natural explanations for the plagues, the sequence and severity of these plagues demonstrate that these were directly from the hand of God. No natural cause would explain why the Egyptians were utterly devastated by these plagues while the Hebrews in neighboring Goshen remained safely untouched, both man and beast (Exodus 8:22; 9:26).

We also have a clue from the only surviving copy of an Egyptian text that has striking parallels to the Exodus account called The Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage, more often known as the Ipuwer Papyrus. Many scholars agree that this is a very early document, some placing it in the 18th Dynasty, the very time of the Exodus (ca. 15th century BC) because of certain linguistic features. The Ipuwer is basically a lengthy poem or prayer to the sun god Ra, written by an Egyptian sage lamenting a series of disasters in the land. I mentioned in my last post that the pharaoh would never let a defeat be recorded in the royal annals. But Ipuwer, the author, seems to be a sage reflecting on the state of the empire he once loved, not a court scribe, because he’s even critical of the pharaoh: “the king has been deposed by the rabble.”[1]

Ipuwer says “pestilence is throughout the land, blood is everywhere, death is not lacking, and the mummy-cloth speaks even before one comes near it.” He writes, “Indeed, the river is blood, yet men drink of it.”

Titus Kennedy neatly sums up the significance of the Ipuwer Papyrus:

“Passages in the poem, such as the river being blood, blood everywhere, plague and pestilence throughout the land, the grain being destroyed, disease causing physical disfigurement, the prevalence of death, mourning throughout the land, rebellion against Ra the sun god, the death of children, the authority of the pharaoh being lost, the gods of Egypt being ineffective and losing a battle, and jewelry now being in the possession of the slaves, are all occurrences in common with the Exodus story.”[2]

To read the Ipuwer Papyrus alongside the Book of Exodus is fascinating. The parallels are simply too clear to downplay. Many scholars have, of course, noted the similarities. However, most have asserted that this reflects a certain genre of “national disaster” folklore at the time rather than concluding that both could be referring to the same historical events. As Hoffmeier observed in the last post, your philosophical presuppositions determine what you will see. The problem with this easy dismissal is that if Ipuwer really was lamenting actual events in history, the above presupposition prevents someone from ever knowing it. One might dare to ask, What would Ipuwer need to say to demonstrate he really was referring to events he witnessed? After all, Ipuwer seems to be talking about a truly devastating time standing in contrast to Egypt’s glorious past.

The Date of the Exodus

There is considerable debate between biblical scholars as to when the Exodus actually took place. Most would place it in either the 15th, 13th, or 12th century BC. Because I take the Bible to be both the authoritative and understandable Word of God, I have no problem accepting the biblical timelines.

One of the clearest statements for dating the Exodus is 1 Kings 6:1: “In the four hundred and eightieth year after the people of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, he began to build the house of the Lord.”

Scholars almost universally agree that Solomon began building the temple in 966 BC. We can then take the 480 years given here, do a little math, and come up with an approximate date of 1446 BC for the Exodus. Scholars who come up with a 12th or 13th century date have to say that the 480 years is a nice round number based on the number of idealized generations, allegedly 40 years each.[3] That strikes me as very strange since there is no indication from the text itself that this is what is going on.[4]

The Pharaoh of the Exodus

Once we have determined the date for the Exodus we can know the most probable pharaoh at this time based on Egyptian chronological records. And we can see if we have any supporting evidence for our dating of the Exodus, too.

According to Exodus, Moses was forced to flee from Egypt after killing an Egyptian guard. Moses spent the next 40 years in the Midianite desert, settling down with his wife Zipporah and becoming a nomadic shepherd.

The Bible says, “After a long time, the king of Egypt died” (Exodus 2:23, HCSB). Later, God tells Moses not to fear returning to Egypt “for all the men who were seeking your life are dead” (Exodus 4:19, ESV). Based on these verses, the pharaoh when Moses fled from Egypt must have been king for a long time, possibly at least forty years.

This is a crucial piece of evidence because most pharaohs did not reign for a very long time. Many didn’t even last ten years. There is, however, one and only one pharaoh in either the 18th or 19th dynasties (the possible eras for the Exodus) who reigned more than forty years, and his name was Thutmose III. According to Egyptian chronologies, that would mean his son, Amenhotep II was the king of Egypt when Moses returned for the Exodus. This is another factor supporting the early date of 1446 BC. The long reign of Thutmose III followed by Amenhotep II reigning at the time of the Exodus in 1446 BC fits together nicely.[5] However, no king during the 13th or 12th centuries reigned 40 years.

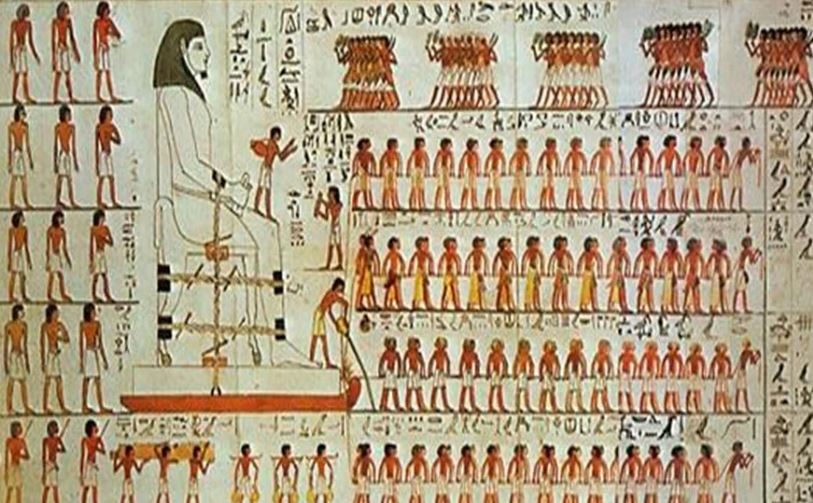

Since there are clues pointing to Amenhotep II being pharaoh at this time, it’s worth considering what we know about him from archaeology. Here’s what’s really intriguing. Amenhotep II was known for unrestrained arrogance of biblical proportions. Archaeologists have found inscriptions and monuments built in his honor where he claimed to be the greatest pharaoh in history. His boasts included rowing a ship faster than 200 Egyptian sailors, shooting an arrow through a copper target as thick as a palm, slaying 7 of the greatest warriors of Kadesh, and capturing more slaves than any other pharaoh in Egyptian history.

This was the pharaoh’s way of saying, “I’m kind of a big deal.” Does this align with what we know about the pharaoh of the Exodus? Well, let’s see. When Moses announced that Yahweh demanded he let the Hebrews go, the pharaoh proudly scoffed, “Who is Yahweh that I should obey Him by letting Israel go? I do not know anything about Yahweh, and besides I will not let Israel go” (Exodus 5:1, HCSB).

Throughout the Exodus narrative (Exodus 5-14), the pharaoh strikes us as arrogant, stubborn, and foolish – almost like someone who was compensating for some major insecurities. Such a psychological profile directly matches everything we know about Amenhotep II.

Evidence for a Crippled Army and Missing Slaves

In addition to his megalomaniacal boasts, Amenhotep II also completed only two military campaigns during the span of his whole reign. This seems strange when you compare it to all his predecessors, who averaged far more military campaigns. Thutmose III, by comparison, led at least 17 campaigns. What would lead the hotheaded Amenhotep II to drastically reduce the number of Egypt’s armed invasions?

Could it be that his once unstoppable army was drastically crippled – even annihilated – in an event at the Red Sea? This circumstantial evidence certainly fits the narrative given in Exodus 14, which says that after the Hebrews left Egypt, Pharaoh changed his mind and sent his entire army in pursuit, including “all Pharaoh’s horses and chariots and horsemen and his army” (Exodus 14:9, ESV). We then read that after Israel had made it safely across the parted Red Sea,

“…the Lord threw them [the Egyptian army] into the sea. The waters came back and covered the chariots and horsemen, the entire army of Pharaoh, that had gone after them into the sea. None of them survived.” (Exodus 14:27-28, HCSB)

It’s worth noting that Scripture never says that Pharaoh himself drowned in the Red Sea, only that his entire army perished. No wonder Amenhotep II had only one campaign after the Exodus.

According to the Elephantine Stele of Amenhotep II inscription, this last campaign was more of a massive slave raid than a conquest of land. Amenhotep II claimed to have captured 101,128 slaves on this raid. If accurate, this would be about 20 times larger than the next largest slave raid in Egyptian history. How interesting that this pharaoh known for ridiculous exaggeration now says he’s also better at bringing in slaves than anyone else! Kennedy observes, “Because this happened right after the Exodus, perhaps it is indicative of an urgent need to replace the lost slave population in Egypt.”[6]

One thing most Exodus scholars agree upon is that future excavations in Egypt will likely shed more light on the timing and details of this central event in Israel’s history. After all, satellite imagery suggests that less than 1 percent of ancient Egypt has actually been excavated to date.[7] The Bible-believing Christian should rejoice in this fact. Once again, archaeological excavations have only strengthened the case for Scripture’s accuracy. We have only examined a portion of the incredible circumstantial evidence that has already been discovered in support of the biblical Exodus.

Have thoughts on this post? Feel free to comment below!

[1] “The Admonitions of Ipuwer,” https://www.worldhistory.org/article/981/the-admonitions-of-ipuwer/

[2] Titus Kennedy, Unearthing the Bible, 55.

[3] This number of 40 years comes from the 40 years of wandering in the desert when a whole generation perished, but that was a specific case not a hard rule that 40 years must always equal one generation in biblical timelines. It’s also worth noting that only those who refused to believe God’s promises perished in the wilderness (Hebrews 3:17), and that the 40 years corresponded with the 40 days they spied out the land (Numbers 14:34). Ironically, supporters of the late view have to take the 40 years mentioned in Numbers 14:34 and Deuteronomy 34:7 literally to make their case, even while they do not take the 480 years given in 1 Kings 6:1 literally.

[4] Other passages supporting the early date of 1446 BC include Judges 11:26.

[5] The problem with the later 13th century or 12th century dates for the Exodus is that in both cases, the pharaoh at those times (Ramesses II or Ramesses III respectively), does not succeed a pharaoh who reigned a long time, which seems to contradict Exodus 2:23.

[6] Kennedy, 57.

[7] Mark Janzen, Five Views on The Exodus, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2021, 16.