Modern scholars often assume the massive migration of Hebrew slaves out of Egypt recorded in the biblical book of Exodus never happened. The Exodus is thought to be nothing more than religious folklore, and that there is no hard evidence for such an event in the ruins of Ancient Egypt.

For example, critical scholars Israel Finkelstein and Neil Silberman claim, “The saga of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt is neither historical truth nor literary fiction… to pin this biblical image down to a single date is to betray the story’s deepest meaning. Passover proves to be not a single event but a continuing experience of national resistance against the powers that be.”[1]

But is this really the case? What can we learn from the actual evidence?

Biblical scholar and archaeologist James K. Hoffmeier has found undue skepticism among many of his peers. He observes, “If it were not still Scripture to Jews and Christians, the Bible probably would not be treated in such a condescending and dismissive manner.”[2]

Egyptologists concede that ancient Egyptians almost never recorded embarrassing losses. The pharaohs always made sure they looked like stellar leaders in the history books. Are we at all surprised? We are, after all, talking about the same human nature that craves approval from peers and longs for affirmation wherever it can get it. Even today, politicians will trumpet their successes but rarely begin a speech discussing their failures. But in Ancient Egypt, the pharaoh controlled the press. That being the case, we really shouldn’t expect to find positive evidence for the biblical Exodus in Egypt’s royal annals.

The remarkable thing, however, is that there is a truckload of circumstantial evidence for the biblical Exodus. I say “circumstantial” because while there may not be much in the way of direct evidence outside of Scripture, the evidence we do have strongly supports the circumstances that would have to be true if such an event were indeed historical.

Another point worth mentioning is that the Bible itself must be properly viewed as crucial evidence for the Exodus event. This may sound obvious, but the scholarly consensus often presupposes the Bible is a book full of myths. This is unwarranted, because an unbiased reading of Exodus reveals a text written as history. Furthermore, outside the Exodus narrative itself (Exodus 1-15), this redemptive event is referenced more than 120 times in the Old Testament. And in every case, the author seems to believe the Exodus really happened and that Moses was the historical man at the helm. In fact, it is the event that explains why Israel is a nation in the first place, and why Israel must serve the Creator-God Yahweh.

Circumstantial Evidence: Hebrews Lived in Egypt

So what is the circumstantial evidence supporting the historicity of the Exodus? One argument used by field archaeologist Titus Kennedy is called “The Point A to Point B argument.” Simply put, if there is good evidence for Hebrews living in Egypt (Point A) before the Exodus on the biblical timeline, and there is also good evidence for Hebrews living in Canaan (Point B) after that time, this would suggest that some kind of mass migration occurred.

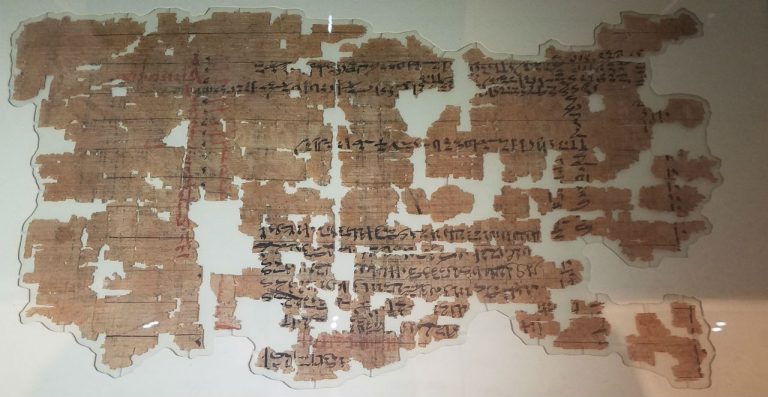

Egyptologists have discovered a list of Semitic servant or slave names on papyrus dated from about the 17th century BC.[3] This list, called Papyrus Brooklyn, gives both the Semitic name of the servant and the Egyptian name they were given. But here’s what’s fascinating. Nine of the servants listed have specifically Hebrew names that can be aligned very closely with other Hebrew names in the Bible. For example, one of the servants is named Shiphrah, the name of one of the Hebrew midwives mentioned in Exodus 1:15. Another servant is even named “Hebrew”!

This papyrus is powerful evidence not only that Semitic people (sometimes called Asiatics) lived in Egypt, but more specifically that Hebrews lived as servants or slaves in Egypt before the biblical Exodus. Interestingly, even critical scholars admit that the evidence points to Semitic people living in Egypt before the date of the Exodus (see Part 2 for a discussion of the Exodus date).[4]

Bricks without Straw

In the Book of Exodus, we read that when Moses first came to Pharaoh demanding he let God’s people go, Pharaoh was insulted. He said that such a demand to be released proved that the Hebrew slaves must be getting lazy. So he commanded his taskmasters to no longer give straw – a necessary ingredient for making bricks – to the slaves, adding that their brick quota would not be reduced. This led to the Hebrew foremen angrily blaming Moses and Aaron for coming to Egypt only to make their hard labor worse (Exodus 5:1-21).

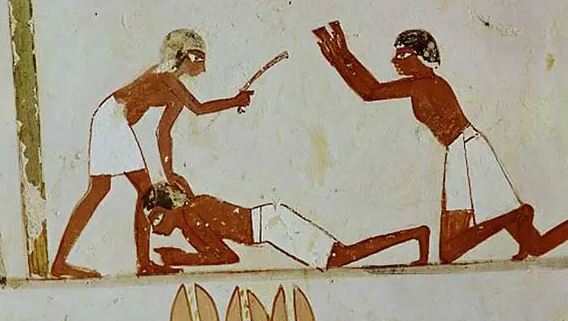

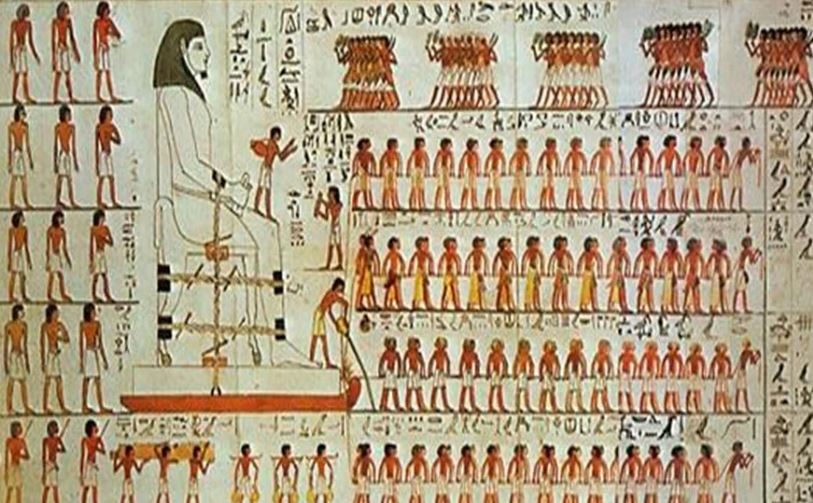

Interestingly, there is a mural on the tomb of Thutmose III, a pharaoh near the time of the Exodus, showing Semitic slaves making bricks. There is also a hieroglyphic text about an Egyptian taskmaster reminding slaves not to be idle or they’ll receive a beating. We also have a wall mural depicting this very thing, lending support to the biblical story of Moses killing a taskmaster who ruthlessly beat a slave (Exodus 2:11-12).

On top of all this, there is also an Egyptian text called the Louvre Leather Roll. Kennedy notes that this text “describes a situation similar to what is recorded in Exodus – that in this time period quotas of bricks were imposed on slaves, but when they did not have the necessary materials to complete all of the bricks, such as a lack of straw, the slaves were punished.”[5]

Did Hebrew Slaves Build the Pyramids?

Some have wondered if the Hebrews had any part in building the pyramids. First, it’s worth noting how much mystery surrounds the building of these massive ancient structures. The largest of the Great Pyramids, called Cheops, consists of 2.3 million stone blocks. These blocks weigh an average of 2.5 tons, with some of the blocks weighing as much as eighty tons! For comparison, the typical 18-wheeler truck can pull up to 24 tons. So, the question is: How in the world did they do it?

The Greek historian Herodotus (484-425 BC) said that when he visited Egypt, he learned that a work force of 100,000 slaves built the pyramids.[6] The Jewish historian Josephus (AD 37-100) said the Egyptian taskmasters “set them [the Hebrews] also to build pyramids.”[7] The consensus of modern scholars, however, is that slaves were not used because there is evidence of a workforce having their own settlement, with their own homes and provisions for all the food they could want.[8] So who is right?

I think it’s impossible to say for sure that Hebrews built the pyramids. But here are some things we do know. Based on the Bible, the Hebrew slaves were used for many massive state projects involving mortar and brick (Exodus 1:10-14). We even have archaeological evidence of a Hebrew slave force in Egypt.[9] There is also a wall mural showing men using ropes to pull massive stones for building the pyramids. One mural seems to depict men using wet sand to help move massive structures.

Again, none of this is conclusive evidence. Most Egyptologists would even date the construction of most of the pyramids to before the Hebrews were even in Egypt. Still, dating methods aren’t infallible; so we can’t rule it out. Scripture never actually claims that the Hebrews built the pyramids, so we shouldn’t be dogmatic on this point. What we can conclude is that a large Hebrew population did live in Egypt prior to the Exodus.

Continue reading in the next post “Is There Evidence for the Exodus? (Part 2)”

Have thoughts on this post? Feel free to comment below!

[1] Finkelstein and Silberman, The Bible Unearthed, 70-71.

[2] James K. Hoffmeier, “The Exodus and Wilderness Narratives,” in Ancient Israel’s History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources, edited by Bill Arnold and Richard Hess, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2014, 48.

[3] Titus Kennedy, Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries that Bring the Bible to Life, 48-49.

[4] Mark Janzen writes, “Egyptologists agree that excavations in the delta reveal a strong Semitic presence during the Hyksos era (ca. 1650-1540 BC), continuing into the New Kingdom.” Janzen, “The Exodus: Sources, Methodology, and Scholarship,” Five Views on The Exodus, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2021, 19.

[5] Kennedy, Unearthing the Bible, 51.

[6] Miroslav Verner. The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt’s Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press, 2001.

[7] Josephus, Antiquities, 11:9.1.

[8] This shouldn’t be used as evidence against the pyramid builders being slaves. The Bible describes the Hebrew slaves as having their own settlement in Goshen (Genesis 47:27; Exodus 8:22; 9:26), having their own homes (Exodus 12:1-13) and eating plenty of delicious food (Numbers 11:5). Perhaps this is one of the ways the pharaohs compensated the Hebrews for their backbreaking work in hopes of preventing an uprising.

[9] James K. Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition.

Pingback: Is There Evidence for the Exodus? (Part 2) – Lamp and Light